Black Holes

Black holes are the cold remnants of former stars, so dense that no matter—not even light—is able to escape their powerful gravitational pull.

While most stars end up as white dwarfs or neutron stars, black holes are the last evolutionary stage in the lifetimes of enormous stars that had been at least 10 or 15 times as massive as our own sun.

When giant stars reach the final stages of their lives they often detonate in cataclysms known as supernovae. Such an explosion scatters most of a star into the void of space but leaves behind a large "cold" remnant on which fusion no longer takes place.

In younger stars, nuclear fusion creates energy and a constant outward pressure that exists in balance with the inward pull of gravity caused by the star's own mass. But in the dead remnants of a massive supernova, no force opposes gravity—so the star begins to collapse in upon itself.

With no force to check gravity, a budding black hole shrinks to zero volume—at which point it is infinitely dense. Even the light from such a star is unable to escape its immense gravitational pull. The star's own light becomes trapped in orbit, and the dark star becomes known as a black hole.

Black holes pull matter and even energy into themselves—but no more so than other stars or cosmic objects of similar mass. That means that a black hole with the mass of our own sun would not "suck" objects into it any more than our own sun does with its own gravitational pull.

Planets, light, and other matter must pass close to a black hole in order to be pulled into its grasp. When they reach a point of no return they are said to have entered the event horizon—the point from which any escape is impossible because it requires moving faster than the speed of light.

Small But Powerful

Usually these stars would be obscured by the gas and dust in that region, but the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile has used its infrared telescopes to peer deep into the black hole's lair. Judging by the orbital trajectories of these 28 stars, astronomers have not only been able to pinpoint the black hole's location, they have also deduced its mass…

It has been long recognised that supermassive black holes probably occupy the centres of most galaxies, from dwarf galaxies to thin galactic disks to large spiral galaxies; the majority of galaxies appear to have them. But actually seeing a black hole is no easy task; astronomers depend on observing the effect a supermassive black hole has on the surrounding gas, dust and stars rather than seeing the object itself (after all, by definition, a black hole is black).

Apart from being the most detailed study of Sagittarius A*'s neighbourhood (the techniques used in this study are six-times more precise than any study before it), the ESO astronomers also deduced the most precise measurement of the distance from the galactic centre to the Solar System; our supermassive black hole lies a safe 27,000 light years away.

Quite simply, the object influencing these stars must be a supermassive black hole, there is no other explanation out there. Does this mean black holes have an even firmer standing as a cosmological "fact" rather than "theory"? It would appear so…

Sources: ESO, BBC

Black holes are invading stars, providing a radical explanation to bright flashes in the universe that are one of the biggest mysteries in astronomy today.

The flashes, known as gamma ray bursts, are beams of high energy radiation – similar to the radiation emitted by explosions of nuclear weapons – produced by jets of plasma from massive dying stars.

The orthodox model for this cosmic jet engine involves plasma being heated by neutrinos in a disk of matter that forms around a black hole, which is created when a star collapses.

But mathematicians at the University of Leeds have come up with a different explanation: the jets come directly from black holes, which can dive into nearby massive stars and devour them.

Their theory is based on recent observations by the Swift satellite which indicates that the central jet engine operates for up to 10,000 seconds - much longer than the neutrino model can explain.

Mathematicians believe that this is evidence for an electromagnetic origin of the jets, i.e. that the jets come directly from a rotating black hole, and that it is the magnetic stresses caused by the rotation that focus and accelerate the jet's flow.

For the mechanism to operate the collapsing star has to be rotating extremely rapidly. This increases the duration of the star's collapse as the gravity is opposed by strong centrifugal forces.

One particularly peculiar way of creating the right conditions involves not a collapsing star but a star invaded by its black hole companion in a binary system. The black hole acts like a parasite, diving into the normal star, spinning it with gravitational forces on its way to the star's centre, and finally eating it from the inside.

Black holes are small in size. A million-solar-mass hole, like that believed to be at the center of some galaxies, would have a radius of just about two million miles (three million kilometers)—only about four times the size of the sun. A black hole with a mass equal to that of the sun would have a two-mile (three-kilometer) radius.

Because they are so small, distant, and dark, black holes cannot be directly observed. Yet scientists have confirmed their long-held suspicions that they exist. This is typically done by measuring mass in a region of the sky and looking for areas of large, dark mass.

Many black holes exist in binary star systems. These holes may continually pull mass from their neighboring star, growing the black hole and shrinking the other star, until the black hole is large and the companion star has completely vanished.

Extremely large black holes may exist at the center of some galaxies—including our own Milky Way. These massive features may have the mass of 10 to 100 billion suns. They are similar to smaller black holes but grow to enormous size because there is so much matter in the center of the galaxy for them to add. Black holes can accrue limitless amounts of matter; they simply become even denser as their mass increases.

Black holes capture the public's imagination and feature prominently in extremely theoretical concepts like wormholes. These "tunnels" could allow rapid travel through space and time—but there is no evidence that they exist.

Beyond Any Reasonable Doubt: A Supermassive Black Hole Lives in Centre of Our Galaxy

One the one hand, this might not be surprising news, but on the other, the implications are startling. A supermassive black hole (called Sagittarius A*) lives at the centre of the Milky Way. This is the conclusion of a 16 year observation campaign of a region right in the centre of our galaxy where 28 stars have been tracked, orbiting a common, invisible point.

Usually these stars would be obscured by the gas and dust in that region, but the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile has used its infrared telescopes to peer deep into the black hole's lair. Judging by the orbital trajectories of these 28 stars, astronomers have not only been able to pinpoint the black hole's location, they have also deduced its mass…

It has been long recognised that supermassive black holes probably occupy the centres of most galaxies, from dwarf galaxies to thin galactic disks to large spiral galaxies; the majority of galaxies appear to have them. But actually seeing a black hole is no easy task; astronomers depend on observing the effect a supermassive black hole has on the surrounding gas, dust and stars rather than seeing the object itself (after all, by definition, a black hole is black).

In 1992, astronomers using the ESO's 3.5-metre New Technology Telescope in Chile turned their attentions on our very own galactic core to begin an unprecedented observation campaign. Since 2002, the 8.2-metre Very Large Telescope (VLT) was also put to use. 16 years later, with over 50 nights of total observation time, the results are in.

By tracking individual stars orbiting a common point, ESO researchers have derived the best empirical evidence yet for the existence of a 4 million solar mass black hole. All the stars are moving rapidly, one star even completed a full orbit within those 16 years, allowing astronomers to indirectly study the mysterious beast driving our galaxy.

Apart from being the most detailed study of Sagittarius A*'s neighbourhood (the techniques used in this study are six-times more precise than any study before it), the ESO astronomers also deduced the most precise measurement of the distance from the galactic centre to the Solar System; our supermassive black hole lies a safe 27,000 light years away.

Quite simply, the object influencing these stars must be a supermassive black hole, there is no other explanation out there. Does this mean black holes have an even firmer standing as a cosmological "fact" rather than "theory"? It would appear so…

Sources: ESO, BBC

Invading black holes explain cosmic flashes

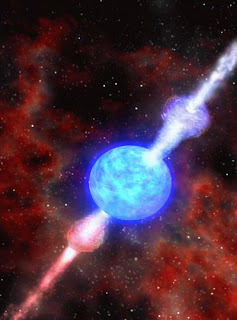

The flashes, known as gamma ray bursts, are beams of high energy radiation – similar to the radiation emitted by explosions of nuclear weapons – produced by jets of plasma from massive dying stars.

The orthodox model for this cosmic jet engine involves plasma being heated by neutrinos in a disk of matter that forms around a black hole, which is created when a star collapses.

But mathematicians at the University of Leeds have come up with a different explanation: the jets come directly from black holes, which can dive into nearby massive stars and devour them.

Their theory is based on recent observations by the Swift satellite which indicates that the central jet engine operates for up to 10,000 seconds - much longer than the neutrino model can explain.

Mathematicians believe that this is evidence for an electromagnetic origin of the jets, i.e. that the jets come directly from a rotating black hole, and that it is the magnetic stresses caused by the rotation that focus and accelerate the jet's flow.

For the mechanism to operate the collapsing star has to be rotating extremely rapidly. This increases the duration of the star's collapse as the gravity is opposed by strong centrifugal forces.

One particularly peculiar way of creating the right conditions involves not a collapsing star but a star invaded by its black hole companion in a binary system. The black hole acts like a parasite, diving into the normal star, spinning it with gravitational forces on its way to the star's centre, and finally eating it from the inside.

The Largest Black Holes in the Universe